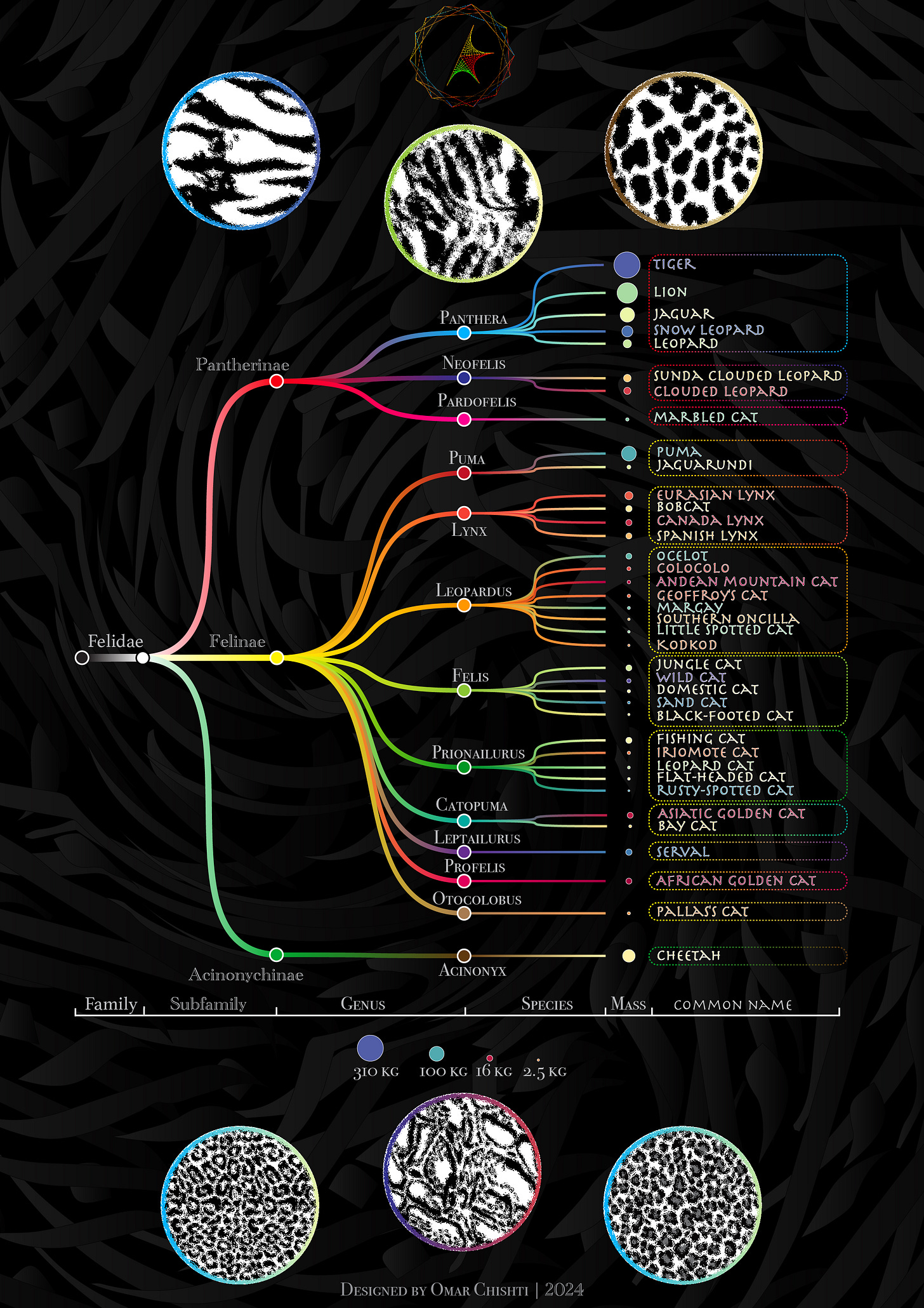

This piece is a bit more whimsical than the rest of the series. It depicts the phylogenetic tree of the Felidae (cat) family using a linear dendrogram. A tree of life, for the feline tree of life. I used slightly outdated data, put together by interns at RawGraphs, which leads to some discrepancies from the generally accepted modern phylogeny (most notably with respect to number of total extant species and the continued placement of Acinonychinae as a separate subfamily). Phylogeny is ever evolving, so the differences didn’t really bother me. I hope they don’t bother you.

38 species in 13 genera from 3 subfamilies. The mass of a representative [male] adult individual from each species is encoded by the area of the circle at the termini of the dendrogram. I assigned a colour to each species, and also to each genus/subfamily.

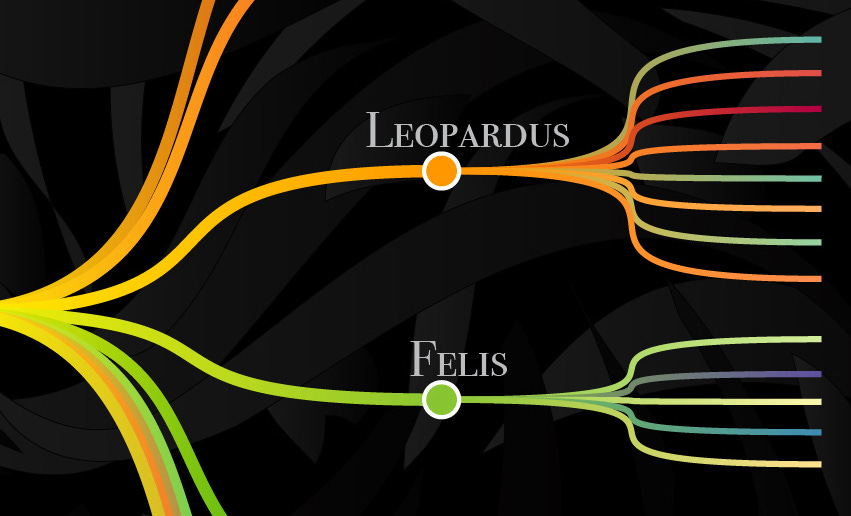

The branches of the dendrogram have a linear gradient fill progressing from the colour of the previous node to the colour of the subsequent node. I assume it’s been implemented elsewhere before, since it is a rather simple idea, but it was my one main novel visual contribution here. Particularly helpful for such phylogenetic trees, since it helps convey the gradual progression of evolutionary changes over time. Divergence from common ancestry. Perhaps I should have applied some colour theory.

Note: Including more general context and fun facts in this write up, since coming across a host of little details was an enjoyable aspect of creating this visual.

The first cats are believed to have emerged 25 million years ago, during the Oligocene. The entire Machairodontinae subfamily (to which the saber-toothed tiger, from the Smilodon genus, belonged) is unfortunately extinct. Smile-odon. Only species in the Panthera genus are called `big cats’. Tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard. The last one is the only one of the five that cannot roar. This set snubs the cheetah, which is technically not a big cat. Just a large one.

I watched a remarkable French documentary about the search for an elusive snow leopard in the Himalayas with a friend from college back in 2021. Only the two of us in the theatre, quite an experience. The Velvet Queen.

There is some David v Goliath action going on amongst all the cats — one of the smallest ones, the black-footed cat, is considered to be the most successful predator of the lot. Its killing instinct dwarfs the lion and the tiger, two massive apex predator cousins with great PR teams and rather disappointing results. Seen all the nature documentaries where the deer gets away? Although there’s probably some survivorship bias for the chosen footage.

Speaking of tigers, I highly recommend taking a safari through Ranthambore National Park (Rajasthan, India) if you’re ever around that corner of the world. Perhaps finding yourself? It’s a large wildlife sanctuary, and the tigers just roam around the jungle.

Here is a picture from my trip back in October 2016:

I varied the stroke width of the dendrogram moving from left to right, to convey the relative breadth of the classification at each level.

“All the branches of a tree at every stage of its height when put together are equal in thickness to the trunk [below them].” — Leonardo da Vinci, Treatise on Painting, 1482-1499

The painter/draughtsman/engineer/scientist/theorist/sculptor/architect sketched out a `Rule of Trees’ centuries ago, and used it for naturalism in his art. It generally states that the thickness of a limb prior to branching is the same as the combined thickness of subsequent branches. Here is a link if you’d like to dive deeper.

This is the principle I implemented to some degree in the dendrogram, which had uniform stroke widths originally. Science has advanced just a little bit since the Renaissance, so there are a few further details uncovered that better mathematically characterise arboreal geometry, but I’ll save it for an upcoming [~two years] Treatise on Trees. Four of you received (suffered?) the broad outlines of some ideas over a meandering walk along the Seine or up at Sacré-Cœur at some point this spring.

There is a little legend below the dendrogram that conveys the technical names for the information presented above. Like the column labels in a spreadsheet, appended at the bottom instead. Not entirely happy with the spacing and so on.

I played with fonts a bit to better distinguish the different kinds of labels. The Devil is in the details, but God is in the serifs. Bit cryptic, as usual, but those two little clauses summarise two of the key things I learnt over my time in Berlin and Paris respectively. Some madness in the methods, some methods to the madness.

Let me know if you’d like more in-depth write ups about the things I learnt. Apparently content of that kind is popular online, especially in neat little list form, but I’m not sure that adequately does justice to the experiential journey. Nuggets of gold are valuable, but wouldn’t it be better to fashion a complete jewellery set? Overall, I’ve begun to realise lately that saving my basket of insight for the ever elongating draft pile of novels/essays (although some does trickle out, in forms like this) while parading my conceit generally isn’t the wisest way to go about things.

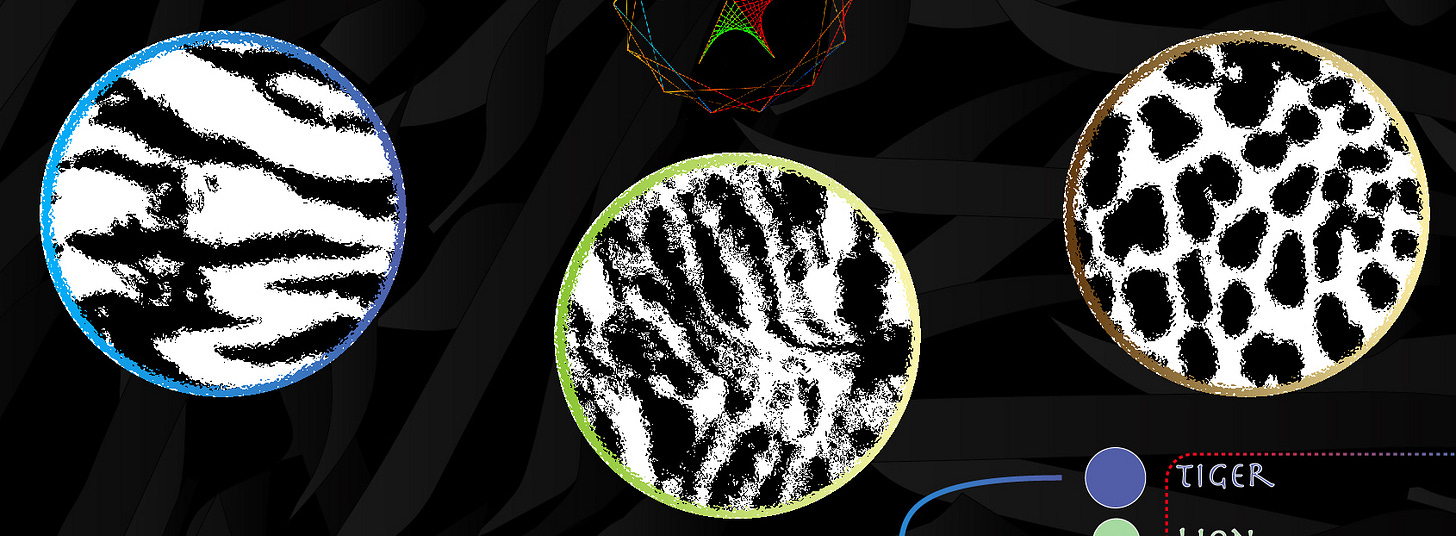

The background, reminiscent of tiger stripes, is meant to represent a ball of yarn, and a curled up cat. If you have a sharp eye you might realise it’s the calligram sun motif I use in all the pieces. There is a set of six circles filling out the negative space that feature the coat patterns for six species. The soft fur and the diverse coat patterns are one of the key distinguishing characteristics of the cat family as a whole.

You can learn interesting things about genetics (specifically Chromosome X inactivation) by looking at the pattern of colours on a calico (tri-colour) cat. They are almost exclusively female, with different colour alleles (black and orange) on either X chromosome. Unpigmented areas are white, pigmented areas with the black X inactivated are orange, while pigmented areas with the orange X inactivated are black. Somatic mosaicism.

Male calicos are exceedingly rare, and are usually a result of either chimerism or a trisomy (extra X chromosome, known as Klinefelter Syndrome in human beings).

Siamese cats with point colouration exhibit acromelanism. They have partial albinism due to a mutated enzyme that helps produce melanin. The mutated tyrosinase is inactive at regular body temperatures, but it works at cooler temperatures. This leads to the white body and the dark face/paws/ears. Physical temperature gradients brought to life by the chemistry of life!

Note: I would add external links to all the terms used but the data dashboard at my end tells me only two or three readers ever click. I assume they are the kind curious enough to Google.

Pictured above is Soviet linguist Yuri Knorozov and his Siamese cat Asya. Yuri is famous for deciphering the Mayan script in 1952. Or making a seminally significant advance, at least. He listed Asya as a co-author on his papers, used this picture as an author photo, and fought a lifelong battle with editors who had the temerity to remove her name and crop out her image. The story has gone viral a few times in posterity. Hard not to find a great man’s undying commitment to his feline familiar inspiring. Muses come in many forms after all. The entire saga is fascinating, especially since it features a “Berlin affair” from WWII.

Moving on, since this write up will get extremely long (endless, even) if I keep peppering in all these random facts and diversions. Classic cat chaos.

I went black-and-white with the fur patterns included in the visualization. I also added a rippled glass texture to better bring out their role in camouflage. Crypsis. One of my college projects for a computational vision course was on that topic.

The colour of the circle’s circumference can help identify which species the pattern comes from, since it is the same gradient stroke as the final branch for a particular species. A few are rather obvious. From left to right, for the three above: a tiger, a domestic cat, and a cheetah.

The domestic cat pattern pictured above is from none other than my [formerly] own kitten Zafran! He’s doing quite well with his new family in New York.

The three circles below come from the leopard, the clouded leopard, and the jaguar [L to R]. I think so, at least — it’s been over a year since I made this. Neat rosettes.

Hope this was a fun foray into the furry feline domain! Think this wraps up the breakdowns of the first set of data visualisations I assembled over the course of 2024.

Side note: I recently set up an account on a website that allows creators to easily elicit support from people who enjoy their work. No plans to solicit Substack subscriptions, since I enjoy sharing things for free (and don’t really have the subscriber numbers that make such things feasible), but you can check out my profile below and become a mini-patron if you’d like.